21 Nov 2025

- 14 Comments

Most people think obesity is just about eating too much and moving too little. But if that were true, losing weight would be simple. The truth is far more complicated. Obesity isn’t a failure of willpower-it’s a biological malfunction. Your brain and body have lost their ability to regulate hunger, fullness, and energy use properly. This isn’t a choice. It’s a disease rooted in how your nervous system, hormones, and fat tissue talk to each other-and when that conversation breaks down, your body starts storing fat even when you’re not eating more.

The Brain’s Hunger Switches Are Stuck

At the center of this problem is a tiny region in your brain called the arcuate nucleus. It’s like the control room for your appetite. Two sets of neurons battle for control: one tells you to stop eating, the other tells you to eat more. The first group, called POMC neurons, releases a signal called alpha-MSH. This signal says, ‘You’re full. Stop.’ It’s powerful-when activated, it cuts food intake by 25 to 40% in animal studies. The other group, NPY and AgRP neurons, screams the opposite: ‘Hunger! Eat now!’ Activate them with a light pulse in a lab, and a mouse will eat 300 to 500% more food in minutes. These neurons don’t work alone. They listen to your body’s hormones. Leptin, made by fat cells, tells your brain, ‘We have enough stored energy.’ In a lean person, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In someone with obesity, those levels jump to 30-60 ng/mL. You’d think more leptin would mean less hunger. But here’s the twist: the brain stops listening. That’s called leptin resistance. It’s not that you don’t have enough leptin. You have too much-and your brain ignores it. This is the core problem in over 99% of obesity cases. Insulin does something similar. After you eat, insulin rises from 5-15 μU/mL to 50-100 μU/mL. Normally, it helps shut down hunger. But in obesity, insulin resistance spreads to the brain. The signals get muffled. Ghrelin, the only known hunger hormone, keeps rising before meals-from 100-200 pg/mL to 800-1000 pg/mL. In obese people, this spike is often higher and lasts longer, making cravings stronger and harder to ignore.Your Body’s Energy Meter Is Broken

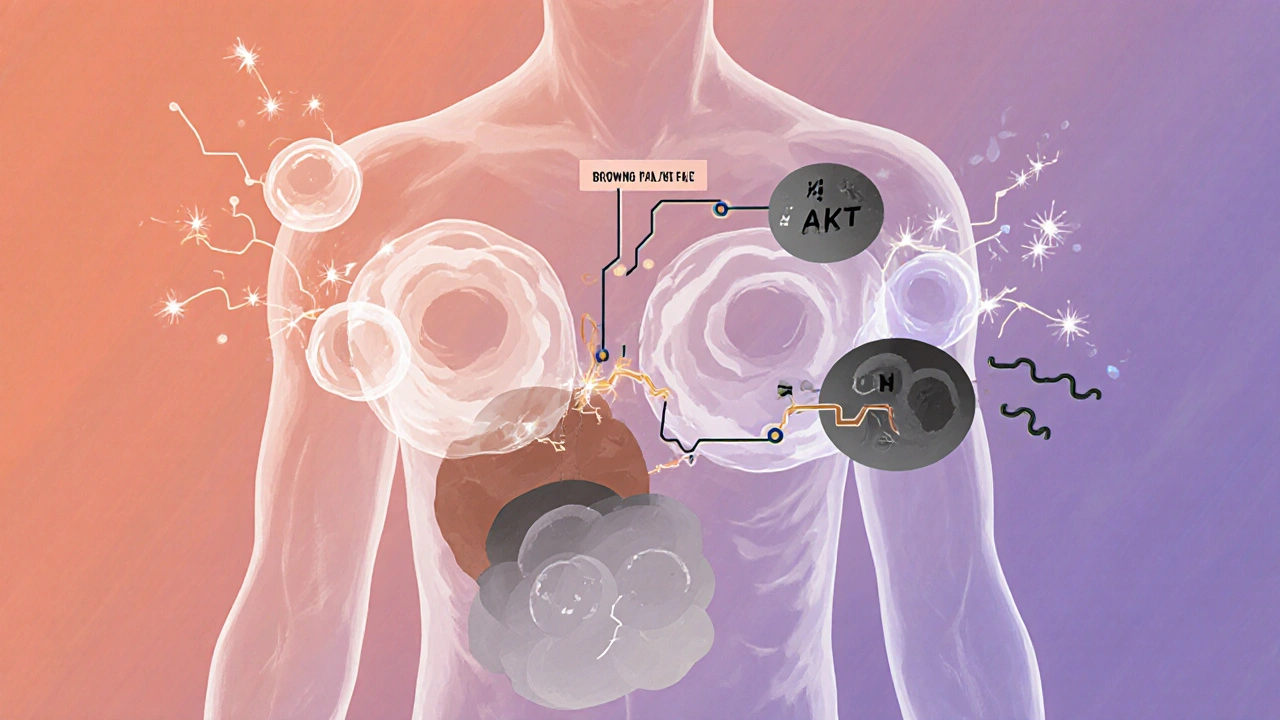

It’s not just about what you eat. It’s about how your body uses what you eat. In a healthy person, excess calories get burned off as heat through brown fat, a type of tissue that turns food into warmth. But in obesity, this system slows down. Your body starts treating extra energy like a savings account-storing it, not spending it. The PI3K/AKT pathway is a key player here. It’s the main line of communication between leptin, insulin, and your appetite neurons. When leptin binds to its receptor, it turns on PI3K/AKT, which then tells POMC neurons to fire and NPY neurons to quiet down. But in obesity, this pathway gets blocked. Inflammation from excess fat activates a protein called JNK, which shuts down the signal. It’s like your brain is trying to say ‘stop eating,’ but the wires are cut. Even the mTOR system, which helps regulate metabolism and aging, gets thrown off. When mTOR is overactive, it makes your body think it’s always fed-even when it’s not. That leads to constant fat storage. Meanwhile, BMP4, a protein that normally helps reduce appetite, drops in obese individuals. When scientists gave BMP4 to obese mice, they ate 20% less and lost weight. That’s not a coincidence-it’s a clue.

Why Diets Fail (It’s Not Your Fault)

When you lose weight, your body fights back. Fat cells shrink, but they don’t disappear. They keep pumping out signals that say, ‘We’re starving!’ Leptin levels drop. Ghrelin rises. Your hunger spikes. Your energy levels crash. This isn’t laziness. It’s biology. Your body is trying to return to its old, heavier set point. And then there’s the reward system. Highly processed foods-rich in sugar, fat, and salt-overstimulate your brain’s pleasure centers. In a healthy brain, the melanocortin system (which includes POMC and MC4R) keeps this in check. But in obesity, that system is worn down. You need more sugar, more salt, more calories to feel satisfied. It’s not a moral failing. It’s a neurological adaptation. This is why most diets fail long-term. You can’t out-eat a broken system. Cutting calories without fixing the underlying biology is like turning off the alarm on a fire alarm without putting out the fire.Gender, Age, and Hormones Change the Game

Women, especially after menopause, face a unique challenge. Estrogen helps regulate fat distribution and energy use. When estrogen drops, fat shifts to the belly, and appetite increases. Studies show post-menopausal women gain 12-15% more belly fat in just five years. In mice without estrogen receptors, food intake jumps 25% and energy use drops 30%. That’s not just about aging-it’s hormonal rewiring. Pancreatic polypeptide (PP), a hormone released after meals, slows digestion and reduces hunger. But in 60% of people with diet-induced obesity, PP levels are abnormally low-half of what they should be. That means fullness signals arrive late, if at all. The same is true for people with Prader-Willi syndrome, a genetic disorder that causes uncontrollable hunger. Their PP levels are even lower. Even sleep matters. Orexin, a brain chemical that keeps you alert, also helps regulate appetite. In obese people, orexin levels are 40% lower. But in night-eating syndrome, orexin spikes at the wrong times-leading to late-night binges. Narcolepsy patients, who have disrupted orexin, are two to three times more likely to be obese. It’s all connected.

Laurie Sala

November 22, 2025This is the most accurate thing I’ve read all year!! I’ve been fighting my body for 12 years-no, not fighting, *begging* it-and no one ever said it like this. Leptin resistance? Yeah. That’s me. I’m not lazy-I’m biologically hijacked. I cry when I see a donut because my brain screams ‘EAT IT’ and my body says ‘NO, YOU’LL REGRET IT’-and I lose every time. I’m not broken. My neurons are just… stuck. Thank you.

Lisa Detanna

November 22, 2025As someone who grew up in a culture where thinness = moral virtue, this changed everything for me. I used to shame my mom for her weight-until I learned her leptin levels were off the charts and her thyroid was silent. We’re not talking about willpower here. We’re talking about neurochemistry. This isn’t a diet problem. It’s a public health crisis disguised as personal failure. We need to stop blaming and start researching.

Demi-Louise Brown

November 23, 2025The science presented here is both rigorous and accessible. The biological mechanisms underlying obesity are complex but well-documented. The focus on neural pathways, hormonal signaling, and metabolic adaptation represents a paradigm shift from behavioral models to neuroendocrinological frameworks. This approach aligns with current clinical research and offers a more compassionate, evidence-based foundation for intervention.

John Mackaill

November 24, 2025I’ve seen this in my patients. One woman lost 80 pounds on a strict keto diet. She felt amazing for six months. Then her body crashed. Her hunger came back worse than ever. She gained it all back plus 20. She wasn’t weak. Her brain just forgot how to stop eating. This post nails it. We need to treat obesity like diabetes-not like a moral test.

Adrian Rios

November 25, 2025Okay, so let me just say this-I’ve been on every diet known to man, from cabbage soup to intermittent fasting to eating only one meal a day at 3 a.m. because I thought that’s what ‘biohackers’ did. And here’s the truth: none of it worked long-term. Not because I gave up. Not because I cheated. But because my brain was screaming ‘FLOOD THE SYSTEM’ while my body was screaming ‘SAVE EVERY CALORIE’-and I was stuck in the middle like a confused toddler with a full cookie jar. Semaglutide? I tried it. I lost 18 pounds in 10 weeks. Not because I ate less. Because my brain finally stopped throwing tantrums. This isn’t magic. It’s medicine. And I’m not ashamed.

Casper van Hoof

November 26, 2025The reduction of obesity to a neurobiological malfunction, while scientifically valid, risks obscuring the sociopolitical dimensions of food systems, economic inequality, and environmental determinants of health. The emphasis on pharmacological interventions may inadvertently reinforce biomedical hegemony over structural reform. One might ask: if the brain is broken, who designed the broken system? The answer is not merely in the arcuate nucleus, but in the agro-industrial complex that engineered hyperpalatable foods to hijack it.

Suresh Ramaiyan

November 27, 2025India has seen a massive rise in obesity in the last 15 years-not because people are eating more rice, but because they’re eating more chips, soda, and fried snacks. The same biology applies here. My uncle, a diabetic, lost 30 kg after starting GLP-1 agonists. He didn’t change his culture. He didn’t stop eating curry. He just fixed his brain’s signal. This isn’t Western medicine-it’s human biology. We need to stop treating this like a moral issue and start treating it like a disease.

Katy Bell

November 27, 2025I’m 38, postpartum, and I gained 50 pounds I can’t lose. I thought it was stress. Or hormones. Or bad luck. But reading this… I finally get it. My body isn’t broken. It’s just been lied to. And now I’m not mad at myself. I’m mad at the system that made me feel guilty for existing. Thank you for saying this out loud.

Vivian C Martinez

November 28, 2025Properly cited mechanisms. Clear delineation of hormonal pathways. Excellent synthesis of current research. The distinction between leptin deficiency and leptin resistance is particularly well-articulated. This is the kind of content that should be required reading for medical students and public health policymakers alike.

Ross Ruprecht

November 28, 2025Ugh. Another ‘it’s not your fault’ post. I lost 60 lbs on my own. Just eat less. Move more. Done. Everyone else just needs to try harder.

Bryson Carroll

November 29, 2025So let me get this straight-your brain is broken so you get to eat whatever you want and call it a disease? Cool. I’ve got a broken ankle but I still don’t get to skip physical therapy. This is just excuse culture dressed up as science. You want to lose weight? Stop eating like a raccoon in a dumpster. Simple. No magic neurons needed.

Kane Ren

November 29, 2025I was told I’d never lose weight after my third kid. I believed it. Then I found out my ghrelin was through the roof and my orexin was low. I started sleeping 8 hours. I stopped eating sugar after 6 p.m. I didn’t count calories. I just listened. Lost 40 pounds in 8 months. Not because I was strong. Because I finally stopped fighting my body and started working with it.

Karla Morales

November 30, 2025OMG this is exactly what I’ve been trying to explain to my family for years 😭 Leptin resistance? YES. Insulin resistance? YES. My body thinks I’m starving even when I’m eating 1200 calories. I’m not lazy. I’m not weak. I’m biologically sabotaged. And now I have a word for it. Thank you. 🙏💖

Javier Rain

November 30, 2025Look, I used to think this was just about discipline. Then I watched my sister take semaglutide and go from 280 to 180 in a year-not by starving herself, but by finally feeling full. She didn’t change her personality. She didn’t become a different person. She just got her brain back. That’s not a miracle. That’s medicine. And if you’re still blaming people for being fat, you’re not just wrong-you’re dangerous.