28 Nov 2025

- 12 Comments

Every time you swallow a pill, inject a shot, or use an inhaler, something complex is happening inside your body. Medicines aren’t magic. They’re chemicals-designed to interact with your body’s own systems in very specific ways. But knowing how medicines work isn’t just for doctors. It’s the key to using them safely, spotting problems early, and avoiding dangerous mistakes.

Medicines Don’t Just Float Around-They Target Specific Sites

Your body has billions of tiny receptors, enzymes, and transporters that control everything from pain signals to blood clotting. Medicines work by locking into these targets like a key in a lock. This is called the mechanism of action-the exact way a drug produces its effect. Take aspirin. It doesn’t just "reduce pain." It blocks an enzyme called COX-1, which makes chemicals that cause inflammation and pain. That’s why it also thins your blood. Same drug, same target, two effects. If you don’t know this, you might take aspirin before surgery and not realize the bleeding risk. Or consider SSRIs like fluoxetine (Prozac). They don’t make you happy directly. They block the reabsorption of serotonin in your brain, leaving more of it available to improve mood. If you suddenly stop taking it, serotonin levels crash. That’s why people get dizziness, nausea, or even electric-shock sensations-not because the drug is "addictive," but because your brain got used to the extra serotonin. Not all drugs work the same way. Antibiotics like penicillin attack bacteria by breaking down their cell walls. Anticoagulants like warfarin block vitamin K, which your body needs to make clotting factors. Cancer drugs like trastuzumab (Herceptin) bind to a protein called HER2 that’s overproduced in some breast cancers. Each drug has its own target, and knowing that target tells you what side effects to watch for.Why Some Medicines Are Riskier Than Others

Not all drugs have well-understood mechanisms. Some were approved decades ago based on observed results, not molecular proof. Lithium, used for bipolar disorder, is one of them. It works-but no one fully knows how. It affects multiple systems in the brain, which is why its safe range is so narrow. Blood levels must stay between 0.6 and 1.2 mmol/L. Go over that, and you risk tremors, confusion, or kidney damage. Under that, and it does nothing. Compare that to statins, like atorvastatin. Their mechanism is clear: they block HMG-CoA reductase, the enzyme that makes cholesterol. Because we know exactly what they do, we can monitor safety. If your cholesterol drops too low or your muscles start aching, we adjust the dose. Patients who understand this are 3.2 times more likely to report muscle pain early-before it turns into rhabdomyolysis, a rare but life-threatening muscle breakdown. Even small changes in a drug’s structure can turn it dangerous. Thalidomide, used in the 1950s for morning sickness, had one form that calmed nausea and another that caused severe birth defects. Back then, scientists didn’t know about enantiomers-mirror-image molecules with different effects. Today, regulators require this level of detail before approval.

What Your Body Does to the Medicine

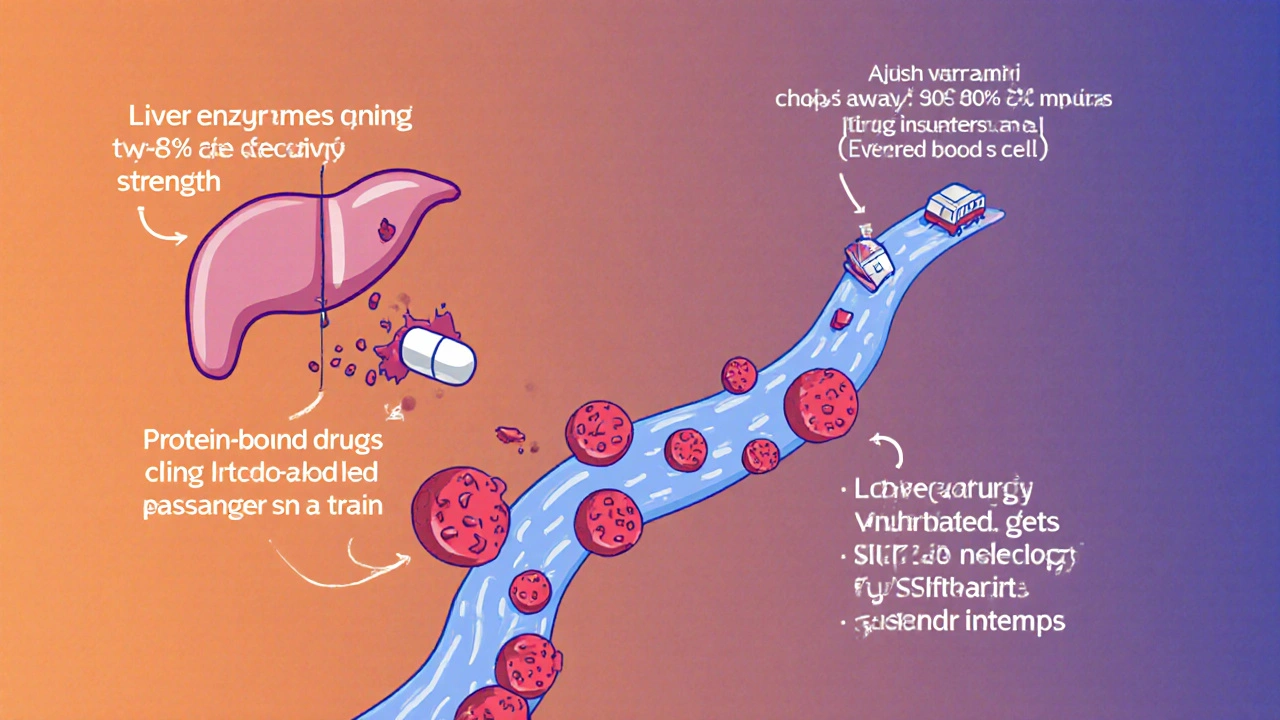

It’s not just about what the drug does to your body. Your body also changes the drug. This is called pharmacokinetics. When you swallow a pill, it goes through your stomach and intestines. Some drugs get broken down by liver enzymes before they even reach your bloodstream. That’s the first-pass effect. Morphine loses about 30% of its strength this way. Propranolol? Up to 90%. That’s why some pills are given in higher doses than others-even if they’re meant to do the same thing. Then there’s protein binding. About 95-98% of many drugs stick to proteins in your blood. Only the small free portion can interact with targets. If another drug comes along that also binds to those proteins-like sulfonamides-it can kick out the warfarin. Suddenly, your free warfarin levels jump 20-30%. That’s when bleeding risks spike. And then there’s the blood-brain barrier. Most drugs can’t cross it. But for Parkinson’s, levodopa (in Sinemet®) is specially designed to sneak through. If you take it with high-protein meals, amino acids compete for the same transporters. The drug doesn’t get absorbed well. That’s why doctors tell you to take it 30 minutes before or after meals.When Medications Are Safe to Use

Safety isn’t just about the drug. It’s about you, your other meds, your diet, your genetics. Take warfarin. It’s safe if you know to avoid large amounts of vitamin K. Spinach, kale, broccoli-these can make warfarin less effective. One cup of cooked kale has over 1,000 mcg of vitamin K. That’s more than five times your daily need. If you suddenly eat a big salad every day, your INR drops. Clots form. If you stop eating greens, your INR spikes. Bleeding happens. Or MAO inhibitors for depression. These drugs stop your body from breaking down tyramine, a compound in aged cheeses, cured meats, and fermented foods. One ounce of blue cheese has up to 5 mg of tyramine. Eat that while on an MAOI? Your blood pressure can skyrocket. Headache, chest pain, stroke risk. Patients who didn’t understand this made up 32% of adverse drug reports to the FDA in 2022. Genetics matter too. About 28% of adverse reactions are linked to gene variants that change how you metabolize drugs. Some people break down codeine too fast and turn it into dangerous levels of morphine. Others don’t break it down at all-it does nothing. The NIH’s All of Us program is now mapping these differences in a million people to make dosing personal.

What You Can Do to Stay Safe

You don’t need a medical degree to use medicines safely. But you do need to ask the right questions.- What does this drug do in my body? Ask for a simple analogy. "SSRIs are like putting a cork in the serotonin recycling tube." That’s clearer than "inhibits serotonin reuptake."

- What foods, supplements, or other meds should I avoid? Don’t assume your pharmacist knows everything. Mention everything-even herbal teas or CBD.

- What’s the early warning sign of a bad reaction? For statins, it’s unexplained muscle pain. For warfarin, it’s unusual bruising or dark stools. Know your red flags.

- Why am I taking this? If you can’t explain the purpose to someone else, you might not be on it for the right reason.

jobin joshua

November 30, 2025Bro this is wild 😍 I just took ibuprofen for my headache and had no idea it was blocking COX-1… now I get why my gums bleed when I brush 😅

Sue Barnes

November 30, 2025Of course you didn’t know. Most people treat pills like candy. You swallow it, hope for the best, and blame the doctor when it backfires. This article should be mandatory in high school. Seriously.

People think 'natural' means safe. Garlic supplements? They thin blood too. Mix that with warfarin? Congrats, you just turned your body into a faucet.

Sachin Agnihotri

December 2, 2025Wow, this is actually super helpful… I never thought about how protein meals mess with levodopa. My dad’s Parkinson’s meds never made sense until now.

Also, the part about SSRIs and serotonin crash? That’s so real. My cousin quit fluoxetine cold turkey and swore she felt like her brain was 'shocking' her. No one told her it was withdrawal.

Can we make a subreddit for this? Like r/DrugMechanicsForDummies? I’d read it every day.

Diana Askew

December 3, 2025They’re hiding the truth. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know how drugs really work - because if you knew, you’d realize they’re just chemical traps.

Did you know lithium was originally used to make salt substitutes? Then they found it calmed people… and suddenly it’s a 'mental health miracle'? Nope. It’s just poisoning your neurons slowly.

And the 'digital twin'? That’s just the next step to tracking you. They’ll inject you with microchips next. I’ve seen the documents.

King Property

December 4, 2025Let me break this down for the people who think 'medicine is magic' - you don’t need a PhD to get this. It’s chemistry. Biology. Physics. Simple.

Statins block HMG-CoA reductase. That’s it. If you don’t know that, you’re not 'just a patient' - you’re a liability. And yes, your kale salad is actively sabotaging your warfarin. Stop pretending you’re too busy to read the damn pamphlet.

And for the love of god, if you’re on MAOIs, don’t eat blue cheese. I don’t care if it’s 'artisanal.' Your brain will thank me later.

Yash Hemrajani

December 6, 2025Oh wow, so now we’re all supposed to become pharmacologists before taking a Tylenol? 😏

Meanwhile, in India, people take 3 different painkillers at once because 'it works better.' And somehow, they live to 90.

But sure, let’s all memorize enzyme names and protein binding percentages. Because nothing says 'healthcare' like turning a simple headache into a molecular biology exam.

Pawittar Singh

December 8, 2025Y’all are overthinking this. 😊

Look - if you don’t know what your med does, ask. Don’t be shy. Pharmacists are there for this. Seriously. I used to be scared to ask questions - until my uncle had a bad reaction because he didn’t tell his doctor he was taking turmeric.

It’s not about being smart. It’s about being safe. And yeah, maybe your doctor’s busy. But you? You’re the one swallowing the pill. Own it.

And if you’re on warfarin? Just keep your greens consistent. One salad a week? Cool. Five? Maybe not. Simple.

We got this. 💪

Josh Evans

December 10, 2025This is actually one of the clearest explanations I’ve ever read. I used to think SSRIs were just 'happy pills' until I read this. Now I get why my friend couldn’t stop crying when she quit.

Also, the part about protein binding and warfarin? Mind blown. I’m going to print this out and give it to my mom. She’s on like 7 meds and never asks questions.

Thanks for writing this. Seriously.

Allison Reed

December 11, 2025This is exactly the kind of education that saves lives. I work in a clinic, and I see patients who’ve been on the same medication for years without understanding why. It’s heartbreaking.

The visual aids mentioned? They’re not optional. They’re essential. A diagram of a receptor binding to a drug - that’s worth a thousand words.

We need this in every prescription packet. Every pharmacy. Every school health class. Knowledge isn’t power - it’s protection.

Jacob Keil

December 12, 2025So… drugs are just keys in locks? Huh. So the whole medical system is just… a lockpicking game? 🤔

And we’re supposed to trust these 'scientists' who still don’t know how lithium works? What if the 'target' isn’t even real? What if it’s all just placebo with extra steps?

And what if the 'digital twin' is just a way to sell you more drugs? I mean… think about it.

They want you to think you’re in control… but really, you’re just another data point.

…I think I’m gonna stop taking my meds. Just to be safe.

Rosy Wilkens

December 12, 2025How dare you normalize this dangerous oversimplification? Medicines are not 'keys' - they are biochemical intrusions into a sacred, complex system that modern science barely understands. This article is dangerously reductionist.

And you dare mention 'digital twins'? That’s the first step toward mandatory biometric compliance. The FDA’s 'Pharmacology 2030' is a Trojan horse for corporate surveillance. Your 'safety' is their profit model.

And your 'simple analogies'? They’re designed to pacify the masses so they don’t question the pharmaceutical oligarchy.

I’ve seen the internal memos. This is not education. It’s conditioning.

Andrea Jones

December 12, 2025Okay, but… what if you’re just tired and your doctor prescribes an SSRI? What if you don’t have the energy to learn all this? 😔

I get it - knowledge is power. But not everyone has the bandwidth. Some of us are just trying to get through the day.

Maybe the real problem isn’t that patients don’t understand - it’s that the system doesn’t make it easy to understand.

So… how do we fix that? Not just tell people to ‘ask more questions’ - but actually make the info accessible? Like, in plain language, on a sticky note?

I’d pay for that app.