28 Dec 2025

- 9 Comments

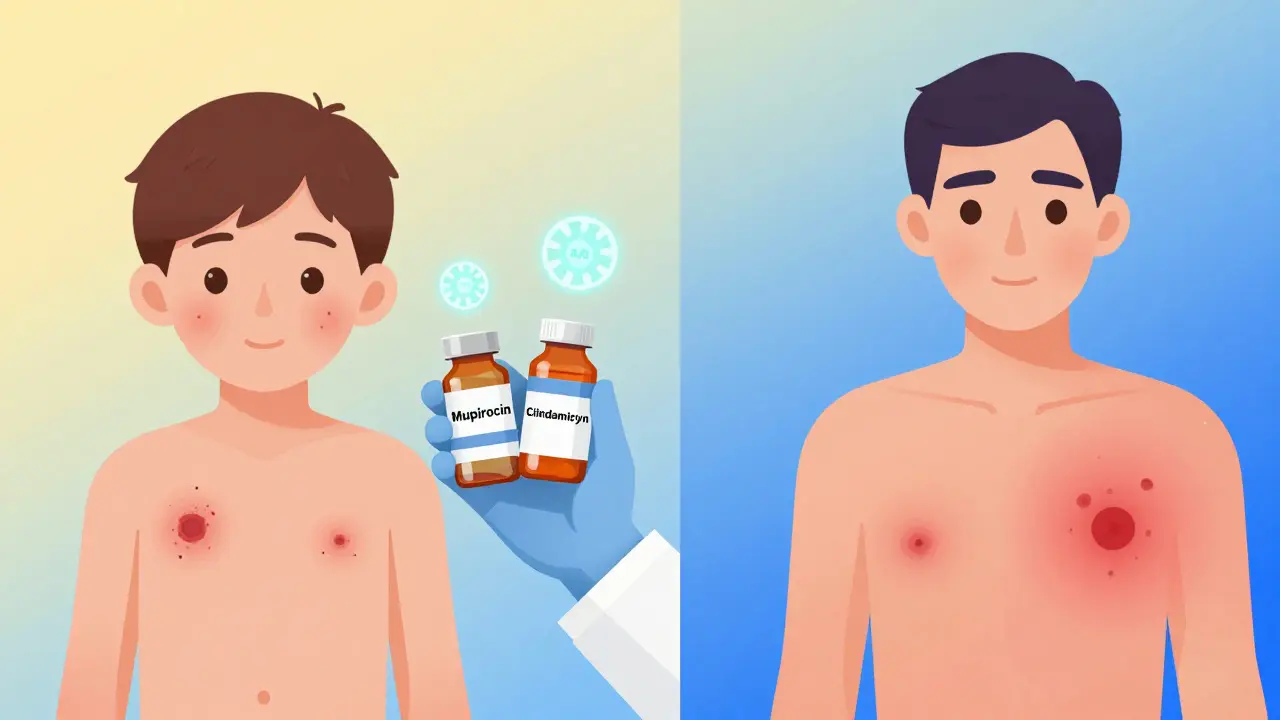

Two of the most common skin infections you’ll hear about in clinics, schools, and emergency rooms are impetigo and cellulitis. They look similar at first glance-red, irritated skin-but they’re not the same. One is mostly a surface problem, often seen in kids. The other digs deep, can turn dangerous fast, and demands serious attention. Getting the right antibiotic isn’t just about following a script-it’s about matching the drug to the bug, the location, and the risk.

What Impetigo Really Looks Like

Impetigo doesn’t start with a big wound. It starts with a tiny scratch, a mosquito bite, or even a patch of eczema that’s been scratched raw. Within a day or two, small red sores appear, usually around the nose and mouth, but also on arms and legs. These sores burst quickly, leaving behind a sticky, honey-colored crust. That’s the classic sign of nonbullous impetigo-the most common type, making up about 70% of cases. The other form, bullous impetigo, is less common. It shows up as larger blisters filled with clear or yellow fluid. These blisters are fragile. When they pop, they leave behind a ring-like border, like a tiny donut of dried skin. Both types are caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes. Kids between 2 and 5 are most at risk. It spreads like wildfire in daycare centers and classrooms. One child with impetigo can infect half a class within a week if no one notices.Cellulitis: When the Infection Goes Deep

Cellulitis is a different beast. It doesn’t form crusts or blisters. Instead, the skin becomes hot, swollen, tight, and painfully tender. The redness doesn’t have clean edges-it bleeds outward, like ink dropped in water. It often shows up on the lower legs, but can appear anywhere: arms, face, even around the eyes. Unlike impetigo, which stays on top, cellulitis invades the dermis and fat layer beneath. That’s why it can cause fever, chills, or swollen lymph nodes. If it’s not treated, it can spread to the bloodstream and cause sepsis. It’s not just a skin problem. People with diabetes, poor circulation, or weakened immune systems are at higher risk. Even a small cut from gardening or a pet scratch can become a portal. Erysipelas, a related condition, looks like cellulitis but has sharp, raised borders and is almost always caused by Streptococcus. Doctors often treat them the same way, but the sharp edge is a clue.Antibiotic Choices: Why One Size Doesn’t Fit All

You might think, “Just give an antibiotic and it’s done.” But the choice matters-big time. The wrong one can fail, or worse, make resistance worse. For impetigo, if it’s limited to a few spots, topical mupirocin works well. It’s applied directly to the skin three times a day for 7 to 10 days. Studies show it clears up about 90% of cases. But if the infection is widespread, or if the person has a fever, oral antibiotics are needed. In the UK and Belgium, flucloxacillin is the go-to. In France, doctors often start with amoxicillin-clavulanate or pristinamycin. Why the difference? Because resistance patterns vary by country. In places where MRSA is common, flucloxacillin won’t work. That’s why cultures are becoming more common in stubborn cases. For cellulitis, oral antibiotics are almost always required. First-line choices depend on where you live. In the UK, flucloxacillin is standard. In France, amoxicillin is increasingly used. Both target Streptococcus, which causes most cases. But if there’s a history of MRSA-like a recent hospital stay, a history of skin abscesses, or living in a community with high MRSA rates-doctors switch to clindamycin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Vancomycin is reserved for severe cases that need hospitalization.MRSA: The Silent Game-Changer

MRSA-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-has changed everything. It doesn’t respond to penicillin, amoxicillin, or flucloxacillin. And it’s no longer just a hospital problem. In many U.S. communities, over 40% of skin infections caused by staph are MRSA. That means if you’ve had a skin infection before that didn’t get better with a standard antibiotic, you might be carrying it. Doctors now ask: “Have you had a skin abscess? Been in the hospital? Had a roommate with a similar infection?” If yes, they skip flucloxacillin and go straight to something that covers MRSA. Culture and sensitivity tests are now used in 65% of recurrent or treatment-resistant cases. That’s a big shift from just 10 years ago, when antibiotics were often prescribed without testing.

How Long Do You Really Need to Take Them?

Most people think: “I feel better, so I’ll stop.” That’s dangerous. Stopping early is one of the top reasons antibiotics stop working. For impetigo, 7 to 10 days is standard-even if the crusts are gone by day 3. For cellulitis, the course is usually 5 to 14 days, depending on how bad it was. If you’re hospitalized, you might start with IV antibiotics, then switch to pills once you’re stable. The rule? Don’t stop until the full course is done. Even if the redness fades, bacteria can still be hiding under the skin.What Happens If You Wait Too Long?

Delaying treatment by more than 48 to 72 hours increases the risk of complications. With impetigo, the infection can spread to other parts of the body or cause kidney inflammation (post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis)-rare, but serious. With cellulitis, the risks are immediate: abscesses, necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating bacteria), or sepsis. One study showed that patients who waited more than 3 days to see a doctor were 3 times more likely to need hospitalization.Prevention: Simple Steps That Make a Big Difference

You can’t always avoid infection, but you can cut your risk way down. - Wash cuts and scrapes with soap and water right away. Don’t let them dry out. Cover them with a bandage. - Never share towels, razors, or clothing. Impetigo spreads through contact with contaminated items. - Keep fingernails short, especially in kids. Scratching spreads bacteria. - If someone in the house has impetigo, wash bedding and clothes daily in hot water. - For people with diabetes or poor circulation, check feet and legs daily for redness, swelling, or breaks in the skin.

When to See a Doctor

You don’t need to rush to the ER for every red spot. But call your doctor if: - The red area is spreading fast (more than 1 inch in 24 hours) - You have a fever, chills, or feel dizzy - The skin feels hard or numb - You’ve had this before and it came back - The infection is on your face, near your eyes, or on a child under 2 - Over-the-counter creams or home care haven’t helped in 2 daysAntibiotic Stewardship: Why We Can’t Just Keep Prescribing

Doctors are under pressure to prescribe antibiotics quickly. But overuse is making them less effective. In the U.S., 20-30% of skin infection prescriptions are unnecessary. That’s why experts now push for “antibiotic stewardship”-using the narrowest, most targeted drug possible. Instead of grabbing amoxicillin or cephalexin for every red patch, doctors are learning to ask: “Is this likely staph? Streptococcus? MRSA?” They’re using local resistance data, patient history, and sometimes rapid tests to choose better. The goal? Cut unnecessary prescriptions by 40% in the next five years. That’s not just about saving money-it’s about saving lives.Can impetigo turn into cellulitis?

Yes, but it’s rare. Impetigo stays on the surface. Cellulitis goes deeper. However, if impetigo is left untreated and the skin breaks further-like from scratching-it can allow bacteria to reach deeper layers and trigger cellulitis. That’s why early treatment matters.

Is impetigo contagious after starting antibiotics?

No, not after 24 hours of starting the right antibiotic. That’s why schools and daycares require kids to stay home until then. After that, the bacteria are no longer spreading easily. But keep the sores covered and avoid touching them.

Can I use over-the-counter antibiotic ointments for impetigo?

Neosporin or similar OTC creams won’t work well for impetigo. They don’t penetrate deeply enough and aren’t strong enough against the bacteria involved. Prescription mupirocin is the only topical option proven to clear it. Don’t waste time with store-bought options.

Why does cellulitis keep coming back in some people?

Recurrent cellulitis is common in people with chronic swelling (lymphedema), poor circulation, obesity, or diabetes. The skin in those areas is more fragile and prone to tiny cracks. Even a small break can become infected. Preventing recurrence means managing the underlying condition-wearing compression socks, keeping skin moisturized, and treating athlete’s foot if present.

Do I need a blood test for cellulitis?

Not always. Doctors usually diagnose cellulitis by looking at the skin. But if you’re very sick, have a fever, or the infection isn’t improving, they may order blood tests or even a culture of fluid from the area to check for MRSA or other resistant bugs.

Bradly Draper

December 28, 2025I had impetigo as a kid and remember how itchy it was. My mom used that pink ointment and kept me home for a week. Didn’t know it could turn into something worse if ignored. Glad this post spells it out so plainly.

Thanks for the heads-up on not sharing towels too. We’ve got two toddlers and I’m definitely changing our laundry habits now.

Gran Badshah

December 29, 2025in india we just use neosporin for everything and pray. no one goes to docs for red skin unless it’s oozing like a volcano. i saw a guy with cellulitis on his leg last year - he waited 3 weeks. his whole calf turned black. hospital saved him but he lost half the muscle. we need better awareness here. no one takes skin infections serious till it’s too late.

Ellen-Cathryn Nash

December 30, 2025It’s absolutely ridiculous that people still think OTC creams are enough for impetigo. It’s not a pimple. It’s a bacterial invasion. And yet, every single day I see moms slathering Neosporin on their kids’ faces like it’s sunscreen. This isn’t ‘natural healing’ - it’s negligence dressed up as holistic care. We’re breeding superbugs by treating symptoms like they’re optional.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘wait and see’ crowd. If your child has honey-colored crusts, you don’t wait 48 hours - you call the doctor before breakfast.

Samantha Hobbs

December 30, 2025OMG YES. My niece had impetigo last year and her daycare said it was ‘just a rash’ and she could stay. I lost it. Like, no. You don’t let a kid with contagious sores near other kids. I had to pull her out and clean the whole house. We went through 3 packs of mupirocin and still had to wash everything in hot water. It’s wild how little people know about this. I’m sharing this post everywhere.

Nicole Beasley

January 1, 2026MRSA is SCARY 😱 I had a friend get it after a tattoo - thought it was just irritation. Then she ended up in the hospital with IV antibiotics for 10 days. No joke. She still gets panic attacks when she sees a red spot. This post is so helpful. I’m saving it for my mom who’s always like ‘it’ll go away on its own’ 💪

Kelsey Youmans

January 2, 2026Thank you for this comprehensive and clinically grounded overview. The distinction between impetigo and cellulitis is often blurred in public discourse, leading to dangerous delays in care. The emphasis on antibiotic stewardship is particularly commendable. In underserved communities, where access to diagnostics remains limited, educational outreach must be prioritized to align community practices with evidence-based guidelines. This is not merely a medical issue - it is a public health imperative.

Celia McTighe

January 3, 2026So many people don’t realize how fast this stuff spreads. My cousin’s daycare had an outbreak last year - 12 kids, 3 teachers. They didn’t even know it was impetigo until the parents started panicking. We started a little ‘skin health’ group in our neighborhood now - just sharing tips, checking in, reminding people to wash hands. Small things, but it helps. Also, I started using the same towel for a week? Yeah, nope. Changed that. 🙃

Ryan Touhill

January 5, 2026Let’s be honest - this whole antibiotic narrative is a distraction. The real issue? The pharmaceutical-industrial complex has been pushing narrow-spectrum drugs as ‘responsible’ while quietly profiting from the rise of resistant strains. They don’t want you to know that silver sulfadiazine or even honey dressings have been proven effective in controlled trials. The FDA and CDC are complicit in this myth of ‘targeted therapy’ - it keeps the pill pipeline flowing. Culture, not chemistry, is the real solution. Wash your hands, stop touching your face, and stop trusting Big Pharma’s playbook.

Teresa Marzo Lostalé

January 7, 2026It’s funny how we treat skin like it’s just a surface - like it doesn’t have memory, doesn’t hold trauma. Cellulitis doesn’t just invade tissue - it invades your sense of safety. Once you’ve had it, you start checking your legs every night like they’re a battlefield. And impetigo? It’s not just a rash. It’s shame. It’s being told you’re ‘unclean’ when it’s just biology. Maybe the real antibiotic is compassion - knowing when to act, when to listen, and when to stop blaming the body for being vulnerable.