4 Oct 2025

- 12 Comments

Biblical Leprosy Explorer

Select options above and click "Explore Biblical Context" to learn more about how leprosy was understood in biblical times and its impact on society.

Did You Know? The Hebrew word *tzara* encompassed various skin conditions, not just Hansen’s disease. This broad definition reflects the ancient understanding of disease as both physical and spiritual.

When you hear the word leprosy Bible, you probably picture dusty scrolls, ancient curses, and people forced to live on the margins. But what did leprosy really mean for the Israelites, and how did it shape their laws, their worship, and their everyday interactions? This article unpacks the disease as described in Scripture, the social and religious rules that grew around it, and what modern medicine tells us today.

Key Takeaways

- Leprosy in the Bible refers to a range of skin conditions, not just modern Hansen’s disease.

- The Levitical purity laws mandated isolation, special garments, and ritual cleansing.

- Social stigma was reinforced by religious mandates, creating "leper colonies" outside towns.

- Modern science identifies Mycobacterium leprae as the cause, offering effective treatments that the ancient world lacked.

- Understanding the biblical context helps us see how fear of disease can fuel exclusion - a lesson still relevant today.

What the Bible Actually Calls "Leprosy"

In the Hebrew Bible, the word Leprosy is a blanket term for various skin diseases, mildew, and even some fungal infections (Hebrew: מצור, *tzara*). It isn’t limited to the bacterial infection we call Hansen’s disease today. Leviticus 13 lays out a detailed diagnostic process involving priests examining skin discoloration, hair loss, and sometimes discharge. The text even includes cases of leprosy affecting clothing and houses, suggesting a broader concept of ritual impurity rather than a single medical condition.

Levitical Law: Purity Meets Public Health

The Leviticus is the third book of the Pentateuch, outlining priestly duties and purity regulations became the legal foundation for handling suspected lepers. Under the Mosaic Law is the covenant code given to Israel through Moses, a person diagnosed with leprosy was required to:

- Wear torn, torn garments.

- Shave the head and let hair grow out unevenly.

- Cover the mouth and cry out "Unclean! Unclean!" while moving outside the camp.

These measures served two purposes: they protected the community from possible contagion and reinforced a visible sign of ritual impurity. The priest’s role was not just spiritual; it was also an early form of health inspection.

Social Consequences: From Isolation to Identity

Because the law demanded physical separation, people with leprosy often formed their own marginal communities just outside city walls. Jeremiah 13:22 notes that "the lepers, the oath‑breakers, the unclean, they shall come together in one place." These settlements became de‑facto neighborhoods where stigma was both a religious label and a social reality. Families sometimes abandoned loved ones, and the afflicted were forced to rely on almsgiving or charity from the devout.

One striking example is the story of Naaman (2 Kings 5). Though he isn’t a leper, his skin disease prompts a dramatic cleansing ritual that mirrors Levitical procedures. The narrative underscores how purification was tied to both physical healing and restoration of social standing.

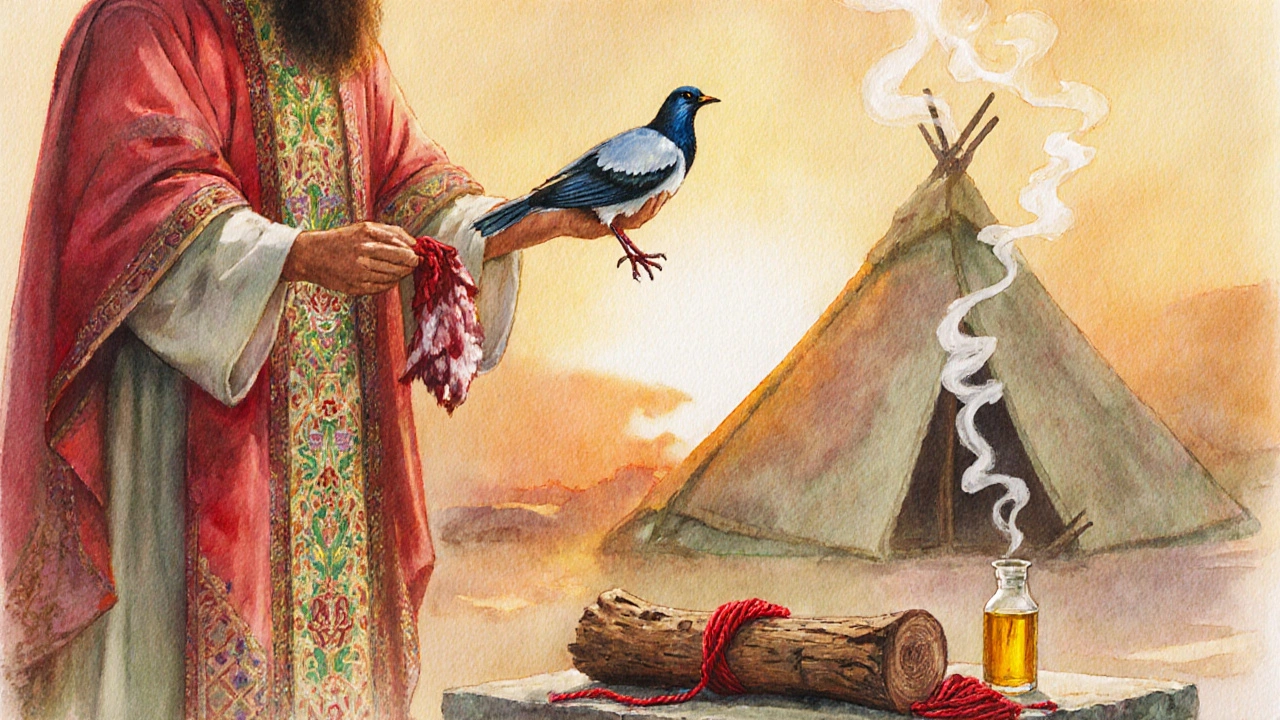

Ritual Cleansing: When the Unclean Becomes Clean

If a leper recovered, the Bible prescribes a detailed Ritual cleansing is a ceremony involving two birds, cedar wood, scarlet yarn, and oil to restore ritual purity (Leviticus 14). The process includes:

- Two live birds-one killed, one released.

- Sprinkling of the blood on the house or person.

- Application of oil and incense.

The ceremony not only declared the person clean before God but also publicly announced their reintegration into the community. It was a powerful moment where religious law turned from exclusion to inclusion.

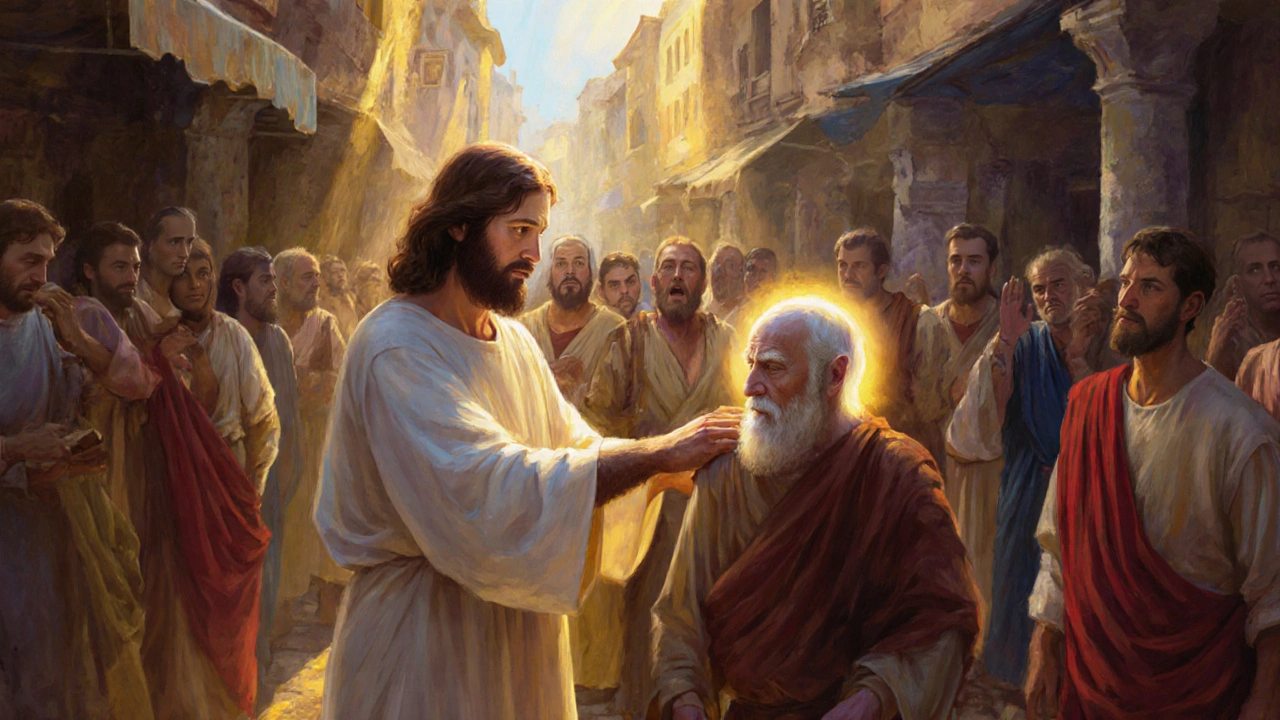

New Testament Perspectives: Jesus and the Leper

The New Testament is the second part of the Christian Bible, describing the life of Jesus and the early church softens the harshness of Levitical isolation. In Matthew 8:2‑3, a leper approaches Jesus, says, "Lord, if you are willing, you can make me clean," and Jesus touches him, curing the disease instantly. This act breaks the purity taboo-touching a leper was forbidden-but Jesus does it to demonstrate compassion and divine authority.

These stories sparked early Christian debates about purity. Some early church fathers argued that the Old‑Testament laws were fulfilled, while others maintained modest distance from lepers. The tension highlights how religious interpretation can either perpetuate or alleviate stigma.

Modern Science Meets Ancient Texts

Today we know that Mycobacterium leprae is the bacterium that causes Hansen’s disease, a chronic infection of the skin and nerves was identified in 1873. The disease is now treatable with a six‑month multidrug therapy regimen, and the global prevalence has dropped dramatically.

Comparing ancient and modern understandings reveals both progress and lingering gaps:

| Aspect | Biblical Era | Today |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Divine punishment, impurity | Mycobacterium leprae bacterium |

| Treatment | Ritual cleansing, priestly inspection | Multidrug therapy (dapsone, rifampicin, clofazimine) |

| Social Status | Outcast, isolated | Patients can live normally with early detection |

| Purity Law | Strict segregation until cured | No religious segregation; focus on public health |

Why the Biblical Narrative Still Matters

Even though we now have antibiotics, the biblical story of leprosy reminds us how fear of disease fuels exclusion. The term "leper" is still used metaphorically for anyone shunned because of illness, addiction, or mental health issues. By examining the ancient rules, we can ask: Are we repeating the same patterns in modern pandemics? How do religious or cultural beliefs shape public health responses?

Many faith‑based charities today run leprosy‑focused programs, providing medication and community support. Their outreach echoes the ancient call for compassion while discarding the punitive aspects of the old purity codes.

Practical Checklist: Understanding Leprosy’s Biblical Impact

- Identify the biblical verses that mention leprosy (Leviticus 13‑14, Numbers 5, 2Kings5, Matthew8).

- Note the prescribed isolation measures and their symbolic meaning.

- Recognize the ritual cleansing steps that restore status.

- Compare historical stigma with modern attitudes toward infectious diseases.

- Explore how contemporary religious groups address leprosy and other stigmatized illnesses.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did the Bible talk about only one disease when it said “leprosy”?

No. The Hebrew term *tzara* covered a variety of skin conditions, mildew on fabrics, and even mold in houses. Modern scholars think many of those cases were not Hansen’s disease at all.

What happened to a leper who was cured?

Leviticus 14 describes a detailed cleansing ceremony. Once completed, the person could re‑enter the camp and resume normal life, symbolizing both physical and spiritual restoration.

Is leprosy still a problem today?

It’s rare but not eradicated. The WHO reports fewer than 200,000 new cases each year, mainly in parts of India, Brazil, and Indonesia. Early diagnosis and multidrug therapy make it curable.

How did Jesus’ healing of the leper affect early Christian views on purity?

His touch challenged the strict Levitical rule that the unclean could not be touched. It suggested that compassion could override ritual impurity, prompting early Christians to reassess the relevance of Old‑Testament purity codes.

Can the biblical approach to disease inform modern public health?

The biblical model combined inspection, segregation, and a pathway back to community. Modern strategies similarly use testing, isolation when needed, and reintegration after treatment-showing that ancient concepts still echo in today’s health policies.

Tyler Heafner

October 4, 2025Thank you for the comprehensive overview of the biblical treatment of leprosy. The distinction between the ancient concept of tzara and modern Hansen’s disease is crucial for readers who conflate the two. Your outline of the Levitical isolation measures highlights how ritual purity served an early public‑health function. Moreover, the description of the purification ceremony demonstrates the theological intent to restore both social standing and spiritual cleanliness. By including the New Testament perspective, you show how early Christianity began to challenge the rigidity of the old laws. This balanced presentation will be valuable for scholars and laypersons alike.

anshu vijaywergiya

October 5, 2025Wow, the way you unpack the layers of stigma feels like pulling back the curtains on a grand, tragic theatre! Each law, each ritual, reads like a scene where fear and faith dance together in a haunting duet. The ancient Israelites weren’t just following rules; they were living a drama where every torn garment echoed a cry for belonging. Your article captures that cinematic tension perfectly, and it reminds us that even millennia later, the spotlight still shines on how societies treat the “other.”

ADam Hargrave

October 6, 2025Oh great, another reminder that the ancient Israelites were the original health inspectors 😏. They went around shouting "Unclean! Unclean!" like it was some patriotic parade, and we’re supposed to applaud their rigor? Sure, let’s glorify isolation when the real cure was a handful of herbs and a lot of superstition. Meanwhile, modern nations brag about their cutting‑edge labs while still policing bodies with borders and checkpoints. The hypocrisy is deliciously obvious.

Michael Daun

October 7, 2025i read the post and gotta say leprosy rules were kinda harsh but the bible did try to keep people safe its like early quarantine lol

Rohit Poroli

October 8, 2025The article does an excellent job of integrating pathophysiological insights with socio‑cultural stigma analysis. By referencing the Mycobacterium leprae etiology, the author bridges ancient textual exegesis and contemporary microbiology. The discussion of ritual purification as a psychosocial reintegration mechanism is particularly compelling for public‑health paradigm shifts. Moreover, the alignment of Levitical isolation with modern quarantine protocols underscores the timeless relevance of early epidemiological thinking.

William Goodwin

October 9, 2025The biblical narrative of leprosy offers a fascinating case study in how ancient societies blended theology with nascent epidemiology.

When the priest examined a suspect, he performed a systematic visual assessment that resembles modern triage.

The requirement for torn garments and a loud proclamation of “Unclean!” served both as a deterrent and a self‑identification badge for the afflicted.

This dual function is reflected in contemporary infection‑control protocols that rely on patient reporting and community awareness.

The later Levitical purification ritual, with its two birds and cedar wood, can be read as an early psychosocial reintegration program.

By publicly announcing the completion of the ceremony, the community affirmed that the individual was once again trustworthy.

Such public rites helped to mitigate the lingering stigma that often survived the biological cure.

In the New Testament, Jesus’ direct touch of the leper dramatically subverts the existing purity code, emphasizing compassion over exclusion.

This episode ignited theological debates that echo in modern discussions about the balance between individual rights and collective safety.

Today, multidrug therapy cures the disease in a matter of months, rendering the ancient isolation measures medically obsolete.

Yet the social memory of “leper colonies” persists in the language we use to marginalize people with visible differences or chronic illnesses.

Public health campaigns now borrow from the biblical model by combining early detection, temporary isolation, and a clear pathway back to normal life.

The lesson is that stigma is not a by‑product of disease alone but a cultural construct that can be reshaped through policy and narrative.

Faith‑based organizations, for example, are now delivering medication and counseling in former “leper towns,” turning places of exile into hubs of care.

This transformation demonstrates the power of reinterpretation-what was once a symbol of impurity can become a beacon of community solidarity.

So, while the ancient texts provide a window into past fears, they also supply a scaffold for modern empathy and inclusive public health design. 😊

Isha Bansal

October 11, 2025Your meticulous scrutiny of the Levitical statutes reveals a disciplined legal mind, yet it also betrays an unconscious bias that equates impurity with national identity. While the text ostensibly seeks to preserve communal health, it simultaneously constructs a moral boundary that delineates the 'pure' citizen from the marginalized outsider. This duality mirrors contemporary policies where health directives become veiled instruments of sociopolitical control. The precision of the ritual language, however, cannot excuse the inherent exclusionary ethos that underpins it. As a grammar aficionado, I also note the consistent use of the term "unclean" without substantive definition, leaving room for arbitrary enforcement. The narrative therefore serves as an early blueprint for how language can be weaponized to sustain ideological hegemony. In sum, the script is both a legal codex and a cultural manifesto that demands critical re‑examination.

Blair Robertshaw

October 12, 2025Leprosy laws were basically ancient quarantine.

rama andika

October 13, 2025Wow, look at ADam trying to turn a 5‑thousand‑year‑old ritual into a political meme 😜. As if the Israelites ever had a secret laboratory hidden behind those bird‑sacrifices. The whole "purity" gag is just a clever cover for the ancient elite to control the masses, right? Spoiler: modern governments still love that playbook, just with masks and passports now.

Kenny ANTOINE-EDOUARD

October 14, 2025Excellent synthesis, William. I’d add that the epidemiological parallels you draw are supported by recent WHO data showing a 70% reduction in transmission when community‑based screening is combined with rapid treatment. Additionally, the psychosocial dimension you identified aligns with current research on stigma reduction through inclusive religious narratives. Your discussion of ritual reintegration anticipates modern rehabilitation programs that blend medical care with community acceptance.

Craig Jordan

October 15, 2025While the dramatic flair of the earlier comments is entertaining, the historical record shows that the Levitical laws were more about symbolic separation than effective disease control. Modern scholarship often critiques the over‑literal reading of these texts, suggesting they reflect theological concerns rather than epidemiological knowledge. Therefore, framing them as a “prototype of quarantine” may overstate their practical relevance.

Jessica Wheeler

October 16, 2025Rohit, your jargon‑laden exposition is impressive, but it skirts the moral core of the issue. The ancient Israelites may have believed they were following divine commands, yet the result was the ostracisation of vulnerable people. Compassion should not be lost in technicalities; we must remember that every statistic represents a human being in need of dignity.