26 Jan 2026

- 12 Comments

PLLR Comparison Tool: Understanding Drug Safety Ratings

Compare Old vs New Drug Safety Ratings

Enter a drug name to see how it was rated under the old A-B-C-D-X system versus the new PLLR system.

For years, doctors and pregnant women were stuck with a simple letter: A, B, C, D, or X. It was supposed to tell you if a drug was safe during pregnancy. But it didn’t. A Category B drug? That didn’t mean it was safe. It just meant no harm was proven in humans - but maybe it hadn’t been tested at all. Meanwhile, a Category C drug, with clear animal risks, was treated like it was dangerous - even if it was the only thing keeping a mother alive. The old system was broken. And it put lives at risk.

What the PLLR Actually Changed

In December 2014, the FDA replaced those letters with something far more useful: detailed, narrative sections. This is the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule, or PLLR. It didn’t just tweak the format. It rewrote how drug safety is communicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Now, every prescription drug label has three clear subsections under Section 8: Pregnancy, Lactation, and Females and Males of Reproductive Potential. No more guessing. No more misleading categories. Just facts - organized, consistent, and designed for real clinical decisions.

Each section follows the same structure: Risk Summary, Clinical Considerations, and Data. That’s it. No fluff. No jargon. Just what you need to know.

Decoding the Pregnancy Section

The Pregnancy subsection (8.1) answers three big questions: What could happen to the baby? What should the doctor do? And where did this info come from?

Risk Summary doesn’t say “probably safe.” It says: “Exposure to this drug during the first trimester has been linked to a 12% increase in neural tube defects based on 47 reported cases.” It tells you if the risk is higher at certain times - like if the drug causes kidney problems only after 20 weeks. It mentions maternal side effects too - like high blood pressure or preterm labor - because a mother’s health affects the baby too.

Clinical Considerations is where the rubber meets the road. It tells you what to do. Should you stop the drug? Switch it? Monitor amniotic fluid levels? For example, some blood pressure meds cause oligohydramnios - low amniotic fluid. The label now says: “Discontinuing the drug led to normalization of amniotic fluid index within 2 weeks in 8 of 10 cases.” That’s not vague. That’s actionable.

Data backs it all up. Animal studies? Human case reports? Registry data? All here. If a drug has a pregnancy exposure registry, it’s listed. These registries are now mandatory - not optional. They collect real-world outcomes from thousands of women. That’s how we know what actually happens.

What the Lactation Section Tells You

The Lactation section (8.2) used to be an afterthought. Now it’s front and center.

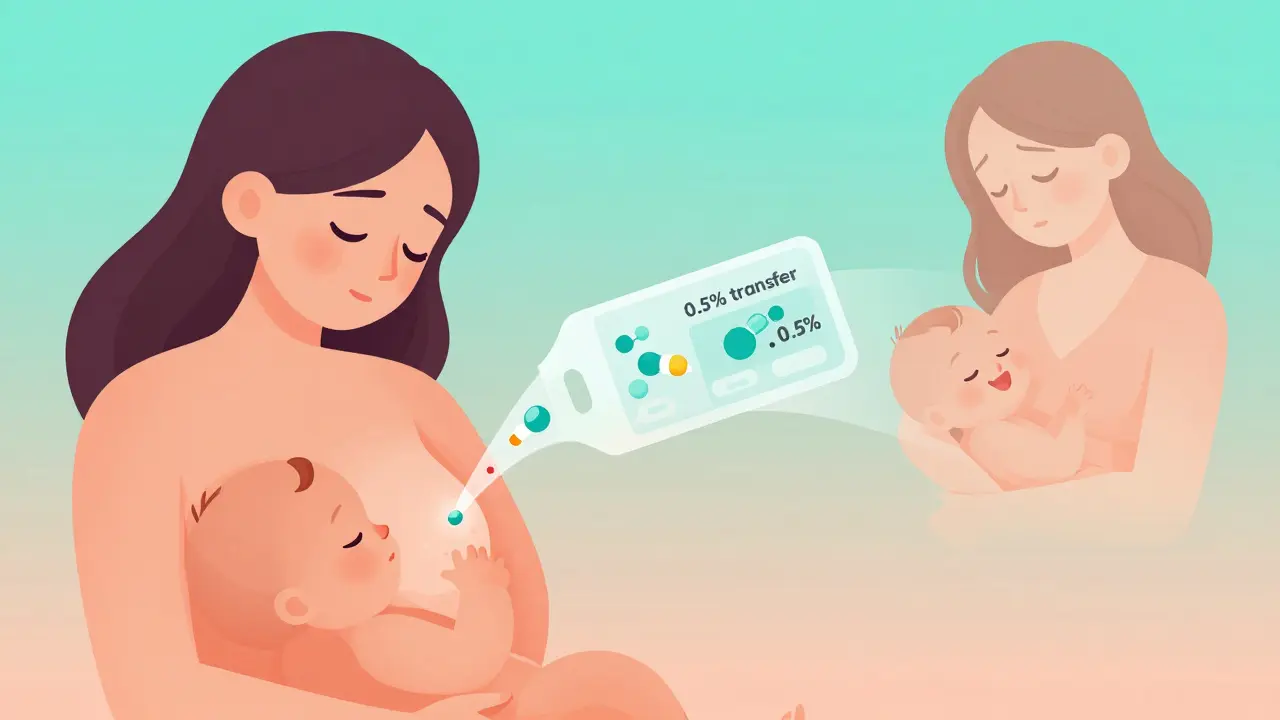

It doesn’t just say “use with caution.” It tells you: How much of the drug gets into breast milk? Is it 0.5% of the mother’s dose? 5%? That makes a huge difference. A drug with 0.1% transfer might be fine. One with 10%? Maybe not.

It also tells you if the drug affects milk supply. Some antidepressants reduce prolactin. Some pain meds make babies sleepy. The label says so - plainly.

And it doesn’t ignore the mother’s needs. It includes: “Untreated depression increases risk of preterm birth and low birth weight.” That’s critical. Sometimes, the risk of not taking the drug is higher than the risk of taking it.

There’s no more “avoid breastfeeding” unless the data clearly shows danger. Most drugs are safe. The label now helps you decide which ones.

Why the Old Letter System Failed

The A-B-C-D-X system was created in 1979. Back then, we didn’t have much data. So they made up categories. But people treated them like gospel.

Category B? “Safe.” Category C? “Dangerous.” But Category B often meant: “No human studies.” Category C meant: “Risks in animals, but no human data.” So a drug with zero testing got labeled safer than one with real, documented side effects.

Doctors got confused. Patients panicked. Pregnant women stopped needed meds - like thyroid pills or seizure drugs - because they saw a “C” and assumed the worst. That led to worse outcomes: uncontrolled epilepsy, miscarriage, preterm birth.

The PLLR fixed that by forcing manufacturers to explain the actual risk - not hide behind a letter.

What’s in the Reproductive Potential Section?

Section 8.3 isn’t just about pregnancy. It’s about planning.

It tells you if you need a pregnancy test before starting the drug. It says if you must use two forms of birth control - and why. Some drugs can cause birth defects even before you know you’re pregnant. So the label says: “Use effective contraception during treatment and for 1 month after stopping.”

It also mentions fertility risks. Some cancer drugs can cause early menopause. Some psychiatric meds affect ovulation. That info used to be buried. Now it’s right there.

This section helps women make informed choices - not just during pregnancy, but before it even starts.

How This Affects Real Patients

Every year in the U.S., about 6 million women get pregnant. More than half take at least one prescription drug. Some take five.

Before PLLR, a woman on lithium for bipolar disorder might have been told: “Avoid this drug.” But the label didn’t say what happened if she stopped. What if her mood crashed? What if she had a psychotic episode? That’s more dangerous than lithium during pregnancy.

Now, the label says: “Discontinuation of lithium increases relapse risk to 70% in the first trimester. Untreated bipolar disorder is associated with higher rates of preterm birth and low birth weight.” That’s not scary. It’s balanced. It helps her and her doctor weigh the real risks.

Same with antidepressants. SSRIs used to be labeled “Category C.” Now the label says: “Transient neonatal adaptation syndrome occurred in 30% of exposed infants, but resolved within 2 weeks. No long-term neurodevelopmental effects were found in follow-up studies.” That’s not a warning. It’s context.

What’s Still Missing

The PLLR is a huge step forward - but it’s not perfect.

Some labels still lack data. Especially for rare drugs or those used in chronic conditions. If there’s no human data, the label says so. But that doesn’t help much. You still need to guess.

And international differences are huge. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) uses different language. A drug labeled “compatible with breastfeeding” in the U.S. might be labeled “not recommended” in Europe. That confuses travelers and expats.

Also, the FDA doesn’t require updates in real time. If new data comes out, manufacturers have to submit it - but it can take months or years to appear on the label.

That’s why doctors still need to check databases like LactMed or MotherToBaby. The label is the starting point - not the end.

How to Use PLLR Labels in Practice

Here’s how to read them like a pro:

- Start with the Risk Summary. What’s the actual risk? Is it rare? Common? Dose-dependent?

- Check Clinical Considerations. What should you do? Monitor? Switch? Stop? When?

- Look at the Data. Is this based on 10 cases or 10,000? Are there registries?

- Read Lactation. How much gets into milk? Does it affect supply or the baby?

- Check Reproductive Potential. Do you need birth control? A pregnancy test?

Don’t just skim. Compare. If you’re unsure, call the pregnancy registry listed on the label. They have experts who can help.

The Bigger Picture

The PLLR didn’t just change labels. It changed how we think about pregnancy and medicine.

Before, drugs were treated like weapons - either safe or dangerous. Now, we treat them like tools. Some are sharp. Some are blunt. Some need careful handling. But none are banned just because they’re risky.

It puts the power back in the hands of the patient and her doctor. Not the FDA. Not the manufacturer. Not a letter on a bottle.

That’s why it matters. Because pregnancy isn’t a condition to be avoided. It’s a time to be supported - with clear, honest, science-backed information.

What does PLLR stand for?

PLLR stands for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule. It’s the FDA’s system for how drug labels must describe risks and safety information for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Are all drugs labeled under PLLR?

Yes, all prescription drugs and biological products approved since June 30, 2001, must follow PLLR. Older drugs had until 2017 to remove the old A-B-C-D-X categories and switch to the new format. Over-the-counter drugs and supplements are not covered.

Can I trust the PLLR label if I’m pregnant?

The PLLR label is the most reliable source of drug safety info during pregnancy - better than the old letter system. But it’s not perfect. Some drugs still have limited data. Always talk to your doctor or pharmacist. Use trusted resources like MotherToBaby or LactMed for extra confirmation.

Does PLLR apply to breastfeeding?

Yes. The Lactation section (8.2) specifically addresses drug levels in breast milk, effects on milk production, and infant safety. It’s designed to help mothers decide if breastfeeding is safe while taking a medication.

What if the label says “no data available”?

That means there’s no human or animal evidence yet. It doesn’t mean the drug is dangerous - just that we don’t know. In those cases, doctors rely on pharmacology (how the drug works), animal studies, and experience with similar drugs. Sometimes, the risk of not treating the condition is higher than the unknown risk of the drug.

Where can I find PLLR-labeled drug information?

The FDA’s website has a searchable database of drug labels. You can also check the prescribing information (PI) that comes with your prescription, or use trusted apps like Micromedex or Lexicomp. The label is always listed under Section 8: Use in Specific Populations.

Candice Hartley

January 28, 2026This is finally how it should’ve been done. No more guessing games. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen too many moms panic over a ‘C’ rating when they needed that med to survive. Thank you, FDA.

Andrew Clausen

January 28, 2026Don’t get fooled by the new format. It’s still corporate PR dressed up as science. The FDA doesn’t require real-world data before approval-just enough to satisfy regulators. The ‘Data’ section is often just a list of underpowered studies with cherry-picked outcomes. Don’t trust the label. Trust your doctor and your instincts.

Anjula Jyala

January 29, 2026PLLR is a semantic overcorrection. Risk Summary must quantify teratogenicity via OR and CI not anecdotal case counts. Clinical Considerations lacks algorithmic guidance. Data section is still fragmented across nonstandardized registries. Lactation transfer % is meaningless without clearance half-life. This is not evidence based it’s bureaucratic theater

Harry Henderson

January 31, 2026STOP acting like this is some revolutionary breakthrough. This was overdue. We’ve been screaming for this since the 90s. Now stop patting yourselves on the back and start pushing for real-time updates. The FDA is still slow as molasses. If your drug label hasn’t changed since 2019, it’s outdated. Demand better.

suhail ahmed

January 31, 2026Man I remember being told to ditch my antidepressant when I got pregnant because it was a ‘C’. My doctor didn’t even ask if I was stable. I went off it cold turkey and ended up in the ER with severe anxiety. The new labels? They’d have said: ‘SSRIs may cause transient neonatal jitteriness but untreated maternal depression triples preterm risk.’ That’s the difference between fear and facts. Thank you for making us think again.

astrid cook

February 2, 2026They say this is progress but let’s be real-this is just another way for Big Pharma to avoid liability. ‘Data’ section says ‘no human studies’? Perfect. That means they can’t be sued if something goes wrong. And don’t get me started on how they bury the worst risks in footnotes. This isn’t transparency. It’s legal camouflage.

Kathy McDaniel

February 3, 2026i just read the pllrr label for my anxiety med and it said ‘transient neonatal symptoms in 30% but resolved in 2 weeks’… and then it said ‘untreated anxiety increases risk of low birth weight’… i cried. i felt seen. thank you for not making me choose between being a mom and being sane

Paul Taylor

February 4, 2026Look I’m all for better info but you gotta understand most patients don’t read the full label. They see ‘risk summary’ and their brain shuts down. They need a one-page cheat sheet. A color-coded system. Something they can glance at in the pharmacy line. The PLLR is brilliant for clinicians but useless for the average person. We need translation not complexity

Desaundrea Morton-Pusey

February 4, 2026Why are we trusting the FDA again? They approved opioids for pregnancy with ‘minimal risk’ and look where that got us. This is just another bureaucratic shell game. They’re not protecting mothers-they’re protecting profits. And don’t even get me started on how they ignore the impact of polypharmacy. Nobody talks about how five ‘safe’ drugs together become a disaster.

Murphy Game

February 5, 2026PLLR? More like PLR-Pregnancy Lie Registry. They’re not giving you data. They’re giving you a script. Every label says ‘no long-term effects’ because the studies haven’t been done yet. They’re betting on time to bury the truth. And the registries? They’re voluntary. Only the brave submit. The rest? Silence. That’s not science. That’s a cover-up.

John O'Brien

February 6, 2026Just had a patient today who was terrified of her blood pressure med because it had a ‘C’ before. She looked up the new label and saw ‘discontinuation led to preeclampsia in 40%’-she started crying. Said she thought she was being selfish for taking it. This system saves lives. Plain and simple. Stop overthinking it. Just use it.

Kegan Powell

February 7, 2026What’s wild is how this changes the whole conversation-not just about safety but about dignity. Before, we treated pregnant women like fragile containers. Now we treat them like people who can handle truth. The PLLR doesn’t just list risks-it acknowledges that sometimes the risk of doing nothing is worse. That’s not just medical. That’s moral. And honestly? It’s the first time I’ve felt proud of how medicine is evolving