15 Jan 2026

- 13 Comments

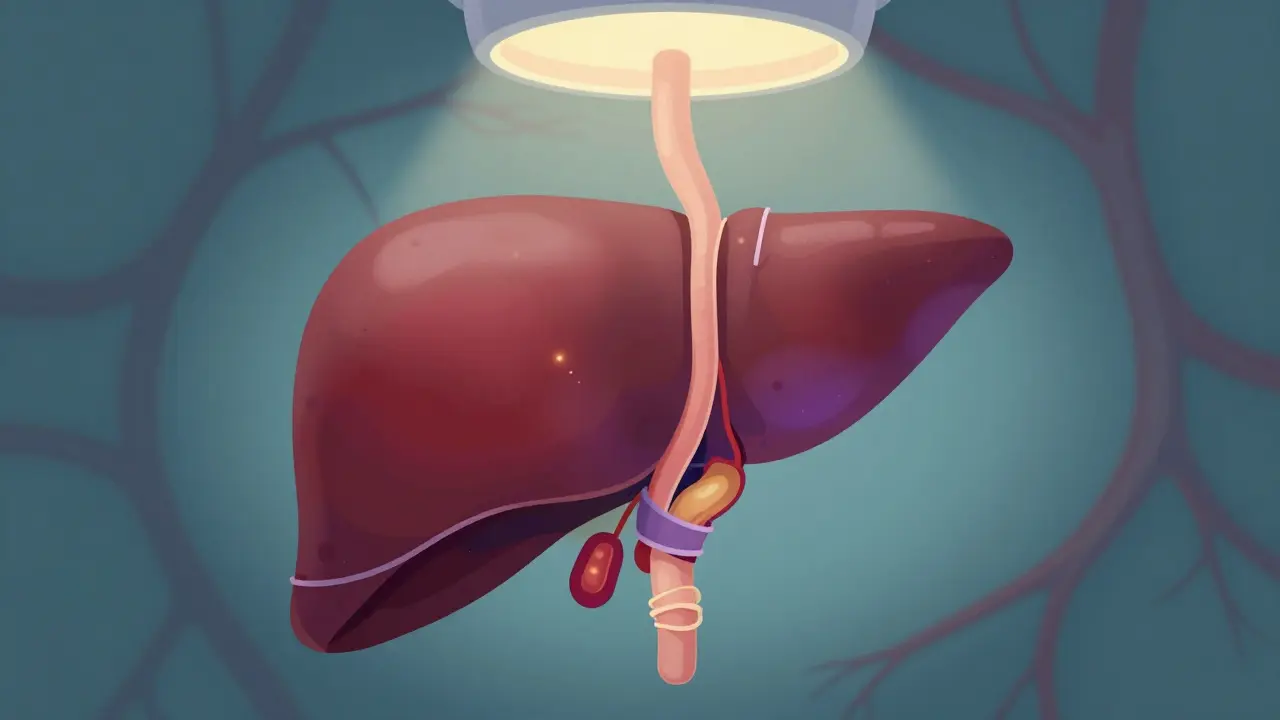

When your liver is damaged by cirrhosis, pressure builds up in the portal vein - the main blood vessel carrying blood from your intestines to your liver. This pressure forces blood to find new paths, creating swollen, fragile veins in your esophagus or stomach. These are called varices. And when they burst, it’s not just a bleed - it’s a medical emergency. About 1 in 5 people who experience variceal bleeding die within six weeks. The good news? We know how to stop it. And we know how to prevent it from happening again.

What Happens During a Variceal Bleed?

Variceal bleeding doesn’t come with warning signs. One moment you’re fine, the next you’re vomiting bright red blood or passing black, tarry stools. Some people feel dizzy, faint, or have a rapid heartbeat. It’s sudden, severe, and requires immediate care. The root cause is almost always advanced liver disease - usually from years of alcohol use, hepatitis B or C, or fatty liver disease. The higher the pressure in the portal vein (above 12 mmHg), the greater the risk of rupture.

Doctors don’t wait to act. The first goal? Stop the bleeding. The second? Prevent it from happening again. And the third? Treat the liver disease behind it. All three steps matter.

Endoscopic Band Ligation: The Gold Standard

When a patient arrives with active bleeding, the fastest and most effective way to stop it is endoscopic band ligation (EBL). This isn’t surgery. It’s done through an endoscope - a thin, flexible tube with a camera - passed down the throat. The doctor uses a device to place tiny rubber bands around the swollen veins. These bands cut off blood flow, causing the varices to shrink and scar over.

Success rates? Around 90-95% for stopping the bleeding right away. That’s why guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases say banding must happen within 12 hours of arrival. Delay it, and the chance of dying goes up.

Most patients need 3 to 4 sessions, spaced 1 to 2 weeks apart, to fully eliminate the varices. Each session takes about 15 to 20 minutes. It’s not pleasant - many report throat soreness, trouble swallowing, or mild chest pain for a week or two afterward. But compared to the old method - injecting chemicals into the veins (sclerotherapy) - banding is safer, more effective, and causes fewer long-term complications like strictures.

Modern multi-band devices, like the Boston Scientific Six-Shot system, let doctors place up to 8 bands in one pass. That cuts procedure time by a third. But it still takes skill. Centers that do more than 50 banding procedures a year have 15% lower rebleeding rates than those that do fewer. Experience matters.

Beta-Blockers: The Silent Shield

Stopping a bleed is urgent. Preventing the next one is just as important. That’s where non-selective beta-blockers (NSBBs) come in. These are pills - usually propranolol or carvedilol - taken daily to lower pressure in the portal vein.

How do they work? They slow your heart rate and reduce blood flow to the liver. This drops portal pressure by 15-25%. The goal? Get the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) down to 12 mmHg or lower, or at least 20% below your starting number. That’s the threshold where bleeding risk drops sharply.

Carvedilol is now preferred over propranolol in many cases. A 2021 study showed it lowers portal pressure more - 22% vs. 15%. And both cut the risk of rebleeding by about half compared to no treatment.

But they’re not for everyone. Side effects are common: fatigue, dizziness, low heart rate. About 1 in 4 patients can’t tolerate the full dose. People with asthma, severe heart failure, or very slow heartbeats should avoid them. And here’s the catch: NSBBs don’t stop active bleeding. They’re for prevention - before the first bleed (primary prevention) or after it’s been stopped (secondary prevention).

Cost is another factor. Generic propranolol runs $4-$10 a month. Carvedilol? $25-$40. For people on tight budgets, that difference matters. Many patients on Reddit say they switched from propranolol to carvedilol because the side effects were less intense - even if the price was higher.

When Banding and Beta-Blockers Aren’t Enough

Not all varices are the same. Banding works great for esophageal varices - the most common type. But if the bleeding comes from the stomach (gastric varices), banding alone often fails. In those cases, doctors may use balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO). This involves threading a catheter into the vein from the leg and injecting glue to seal it off. Studies show BRTO cuts 30-day mortality nearly in half compared to banding alone for gastric varices.

Then there’s TIPS - transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. This is a metal stent placed inside the liver to create a new channel for blood to bypass the blocked portal vein. It’s powerful. In high-risk patients - those with Child-Pugh B or C cirrhosis - TIPS boosts one-year survival from 61% to 86%. But it comes with a big risk: hepatic encephalopathy. Up to 30% of patients develop confusion, memory problems, or even coma because toxins that the liver can’t filter now flow straight to the brain.

So TIPS isn’t for everyone. It’s reserved for those who keep rebleeding despite banding and beta-blockers - or those who are at very high risk from the start. Only 45% of U.S. hospitals can do it within 24 hours because it requires specialized radiologists and equipment.

What About Other Drugs?

While beta-blockers are for long-term prevention, vasoactive drugs like terlipressin and octreotide are used during active bleeding. They narrow blood vessels in the gut, reducing pressure fast. Terlipressin reduces death risk by 34% compared to no treatment. Octreotide works just as well in real-world settings and is easier to use - no need for constant IV drips.

Now there’s a new option: Sandostatin LAR, a long-acting octreotide shot given once a month instead of daily. Early data suggests it could improve adherence - right now, only 62% of patients stick with daily injections. That’s a big deal for people already juggling multiple meds and doctor visits.

Prevention Is the Real Win

The best way to avoid variceal bleeding? Prevent cirrhosis from getting worse. That means stopping alcohol, treating hepatitis, losing weight if you have fatty liver, and getting regular monitoring. If you have cirrhosis, your doctor should check for varices with an endoscopy every 1-2 years. If you have medium or large varices, you should be on a beta-blocker - even if you’ve never bled.

But prevention isn’t just about medicine. It’s about support. Patients who use nurse navigator programs - like those offered by the American Liver Foundation - are more likely to keep appointments, take their meds, and avoid hospital readmissions. One patient said it best: “I dread the banding appointments every two weeks, but I know it’s saving my life.”

The Bigger Picture

Each year, 250,000 Americans have variceal bleeds. The cost? Over $2.8 billion. The global market for treatments is growing fast - expected to hit $1.8 billion by 2028. But access isn’t equal. In Asia, sclerotherapy is still common because it’s cheaper. In the U.S., banding is standard - but only if you get to the hospital fast enough. Only 68% of patients get endoscopy within the critical 12-hour window.

And disparities are real. Uninsured patients are 35% more likely to die from variceal bleeding than those with insurance. That’s not a medical problem - it’s a system problem.

Looking ahead, AI tools are being tested to predict who’s most likely to bleed next - based on liver scans, blood tests, and vital signs. If we can spot danger before it happens, we might cut deaths by 40% in the next decade. But until then, the tools we have - banding, beta-blockers, and timely care - are still the best defense we have.

What You Can Do

- If you have cirrhosis, ask your doctor for an endoscopy to check for varices.

- If you’re on beta-blockers and feel too tired to function, talk to your doctor. Dosing can be adjusted. Carvedilol might be a better fit.

- Don’t skip banding sessions. Even if you feel fine, the varices are still there.

- Know the signs of bleeding: vomiting blood, black stools, dizziness. Call 911 immediately.

- Connect with patient support groups. You’re not alone - and shared experience saves lives.

Can variceal bleeding be prevented entirely?

Not always - but the risk can be reduced dramatically. If you have cirrhosis, regular endoscopy and taking beta-blockers like carvedilol or propranolol can lower your chance of bleeding by up to 50%. Avoiding alcohol, managing hepatitis, and controlling weight are also critical. For people with large varices, even without prior bleeding, banding may be recommended to prevent the first bleed.

How long does it take for beta-blockers to work?

They start lowering heart rate and blood pressure within hours, but it takes weeks to reach the full effect on portal pressure. Doctors usually start with a low dose and slowly increase it over 1-2 months to avoid side effects. The goal isn’t just to feel better - it’s to get your hepatic venous pressure gradient down to 12 mmHg or lower. That’s when bleeding risk drops significantly.

Is endoscopic banding painful?

The procedure itself is done under sedation, so you won’t feel it. Afterward, most people have mild throat soreness, like a bad sore throat, for a few days. Some describe a dull chest ache or trouble swallowing solid food for up to two weeks. It’s uncomfortable, but it’s not the same as surgery. Severe pain or fever after banding should be reported immediately - it could signal a complication like a perforation or infection.

Why is carvedilol preferred over propranolol?

Carvedilol lowers portal pressure more effectively than propranolol - about 22% versus 15% in head-to-head trials. It also has additional effects on blood vessels that may help reduce liver damage over time. While both cut rebleeding risk by about half, carvedilol’s stronger pressure-lowering effect makes it the preferred choice for primary prevention in high-risk patients. The downside? It’s more expensive, and not all insurance plans cover it at the same level.

Can I stop taking beta-blockers if I’ve had successful banding?

No. Even after all varices are gone, the underlying portal hypertension remains. Stopping beta-blockers raises your risk of rebleeding - even if the veins are gone. Studies show that stopping NSBBs increases rebleeding risk by 3-4 times. You’ll likely need to stay on them for life, unless your liver function improves dramatically - such as after a successful transplant.

What happens if I miss a dose of my beta-blocker?

If you miss one dose, take it as soon as you remember - unless it’s close to your next scheduled dose. Don’t double up. Missing doses occasionally isn’t likely to cause immediate bleeding, but it reduces the protective effect over time. Consistency matters. If you’re struggling to remember, use a pill organizer or set phone reminders. Talk to your pharmacist about once-daily options if you’re on multiple medications.

Next Steps and Troubleshooting

If you’re newly diagnosed with cirrhosis and varices, start with an endoscopy and a beta-blocker. Ask your doctor: “What’s my HVPG? What’s my bleeding risk?” If you’ve had a bleed, confirm you’re on both banding and beta-blockers - not just one. If you’re struggling with side effects, don’t quit. Ask about alternatives like carvedilol or dose adjustments.

If you’re a caregiver, help track medications, appointments, and symptoms. Fatigue, confusion, or swelling in the legs could mean your loved one’s condition is worsening. Don’t wait for a crisis - call the doctor early.

And if you’re in a rural area without easy access to specialists, reach out to the American Liver Foundation’s nurse navigator program. They help connect patients with local resources, transportation, and insurance support - no matter where you live.

Ayush Pareek

January 15, 2026Been on carvedilol for 18 months now. Side effects? Yeah, I get tired. But I’ve had zero bleeds since starting. Banding sessions suck, but they’re my lifeline. If you’re scared, just remember: every session is one less time you’ll wake up vomiting blood.

Nilesh Khedekar

January 17, 2026Oh wow, another ‘trust your doctor’ sermon… Meanwhile, in India, 70% of patients can’t even afford propranolol, let alone carvedilol. And don’t get me started on ‘specialized radiologists’-half the country doesn’t even have a gastroenterologist who’s seen a varix in person. This post reads like a pharma ad disguised as medicine.

Nat Young

January 18, 2026Let’s be real-banding isn’t the ‘gold standard.’ It’s the default because it’s profitable. Sclerotherapy is cheaper, safer in resource-limited settings, and has just as good long-term outcomes if done properly. The AASLD guidelines? Written by people who own endoscopy centers. Also, ‘TIPS boosts survival’? Only if you ignore the 30% who end up in a vegetative state from hepatic encephalopathy. This isn’t medicine-it’s triage capitalism.

Jan Hess

January 18, 2026Just wanted to say thank you for this. I was scared to start beta-blockers because I thought they’d make me useless. Turns out, I just needed the right dose. Carvedilol changed my life. I’m hiking again. I’m sleeping. I’m not dying. Keep showing up for your health. You’ve got this.

Iona Jane

January 20, 2026They’re hiding the truth. Banding? It’s not to save you-it’s to keep you dependent. The liver doesn’t heal because they want you on meds forever. Big Pharma owns the guidelines. They don’t want you cured. They want you on carvedilol until your kidneys fail. I’ve seen the documents. They know.

Jaspreet Kaur Chana

January 21, 2026Bro, I’m from Punjab, my uncle had cirrhosis from years of liquor, no insurance, no access to endoscopy-so he drank more because he thought ‘what’s the point?’ Then he bled out in a village clinic. If someone had just told him ‘get checked every year’ or ‘take this cheap pill’-he’d still be here. This isn’t just medical advice. It’s survival. Don’t wait until you’re vomiting blood to care.

Diane Hendriks

January 21, 2026It is deeply concerning that the article implicitly endorses a Western biomedical paradigm as universally applicable. In non-Western contexts, holistic approaches-such as Ayurvedic hepatoprotectives like Phyllanthus niruri or dietary modifications rooted in traditional knowledge-are not merely alternatives-they are culturally embedded, empirically validated, and economically sustainable. The dismissal of these modalities is not clinical-it is colonial.

Annie Choi

January 22, 2026AI predicting bleeds? Yes please. But let’s not pretend tech will fix what policy broke. If you’re uninsured, you’re already dead in this system. I work in ER. We see it every week: the guy who waited three days because he didn’t have a ride. The woman who skipped meds because she had to choose between insulin and her beta-blocker. Banding won’t help if you can’t get to the hospital. We need healthcare as a right-not a privilege.

Arjun Seth

January 22, 2026You people are so naive. You think taking a pill makes you safe? You’re just a walking time bomb. Your liver is already dead. Banding? It’s a band-aid on a severed artery. You’re not ‘managing’-you’re delaying the inevitable. Stop lying to yourself. The only real fix is quitting alcohol. But you won’t. You’re addicted. And now you want a magic pill. Pathetic.

Dan Mack

January 24, 2026They don’t tell you that TIPS is basically a suicide pact with a stent. I know a guy who got one. He went from ‘I can walk to the fridge’ to ‘I don’t know who my daughter is’ in six weeks. And the doctors? They just shrugged. ‘It’s better than bleeding out.’ No. It’s not better. It’s just quieter. They’re selling sedation as salvation.

Amy Vickberg

January 24, 2026Just wanted to add-my mom was on propranolol for 5 years. Switched to carvedilol after her doctor listened. Her energy came back. She started gardening again. Don’t let side effects silence you. Ask for help. There’s always a better fit. You’re worth the effort.

Nishant Garg

January 25, 2026Look, I’ve been through this. Banding every two weeks. Pills twice a day. Blood tests. Diet changes. It’s exhausting. But here’s the thing-it’s not about being strong. It’s about showing up. Even when you’re tired. Even when you hate it. Even when you think nobody cares. I’m still here. So are you. And that’s the win.

Nicholas Urmaza

January 26, 2026The data is clear. Banding within 12 hours reduces mortality by 40 percent. Beta blockers reduce rebleeding by 50 percent. These are not opinions. They are evidence based standards. Dismissing them because of cost or access is not advocacy. It is negligence.